I have the privilege of teaching a fantastic group of writers this fall, and last night they reminded me of just how insidious our cultural ideas of what it means to be industrious can be. Within seconds of my asking them what industry looks like, they came up with so many of those loaded words that don’t just fail to define the creative process, but actively work against it. Words like efficiency; productivity; reproduceable results.

I said it then and I’ll say it now: a great way to know that you’re not fully engaged in the creative process is to keep tabs on how efficient, productive, and easily translatable your work is. Naturally, these might not be the adjectives you’d use, but how many of us worry about how quickly our work is moving along, or if we’re getting enough done, or how likely it is we can attract the attention of countless adoring readers or have it converted to a wildly popular HBO series? You don’t have to answer those last questions aloud. But I have yet to meet the writer who doesn’t dwell occasionally in the fantasy land of realizing Rowlingesque popularity. We were, after all, usually the ones with glasses who chose to read in a comfy corner when everyone else was out playing tag football, so it’s only natural that we might be hungry for a few more people to see and celebrate the world the way we do.

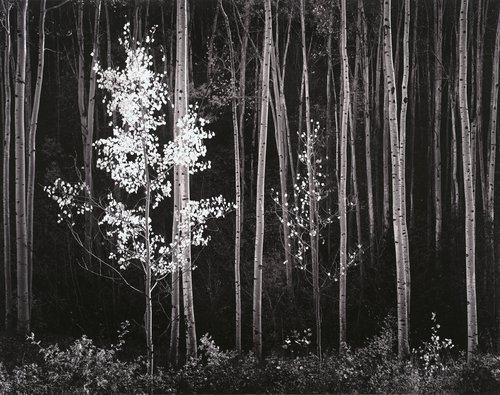

That said, it’s just as important that we see how these unhelpful notions of industry are controlling our puppet strings as it is that we avoid them. In other words, in order to tame the beast, you must be willing to see it in all its grisly and backlit glory. What’s more, you will need to regularly revisit the terrain it wanders, being ever vigilant about protecting your creative space from culturally embedded, directly oppositional ideas of what it means to be worthwhile and productive.

Creative work thrives around a willingness to engage uncertainty, to invest in growth instead of product, to keep your mental playground open to discovery, surprise, and emotional truth. As such, it is far more organic than man-made, and whenever we try to force ideas of good work that stem from 20th century factories down its throat, it’s no wonder that it seizes up like an abruptly boneless toddler who has decided that leaving for preschool is no better than being boiled alive. Why does it react with such petulance and immaturity? Because if you continue to ignore its messages in favor of keeping up with J.K. Joneses, it’ll respond accordingly.

If, on the other hand, you treat it as you would tend a garden that might yield the kind of life-giving sustenance you cannot survive without, you’ll enter into an entirely different kind of exchange. If you plant seeds gently and attentively when you’re just starting out, showing gratitude for even the smallest signs of something taking root in the soil you’ve cultivated according to the climate and conditions that work best for it, you will see astonishing things sprout almost overnight. If you go on to shape these wonders according to how well their leaves can receive the light of the sun, you will find eventually see a harvest of extraordinary abundance. And if, after that harvest, you allow for the time your creative soil needs to go fallow and rework its magic in depths far beyond the limitations of the human eye, when renewal tugs at your sleeve yet again, will be more prepared than ever to sow those marvelous new oddities only you can grow.

Wow…makes me wnt to write…hmmm…

Hemmingway was a very industrious and disciplined writer … it worked for him … different strokes for different folks …

Hemingway had book contracts and monetary advances. So there was a powerful incentive for him, unlike the unknown scribe who has absolutely no indication of payoffs.