Today I want to talk about practice because it is just so unbelievably, tooth-pullingly, maddeningly hard. We’re designed to grow, right? We all want to get better at the things that are important to us, right? And we all know that only through genuine practice – showing up and putting in face time with those parts of us that could benefit from a little improvement – will we get any better at anything worthwhile. It should be a no brainer, something we come to eagerly, knowing how it can get us through over the worst humps or blocks. And yet most days, convincing yourself to practice – whether that be honing some shaky job skills, or starting that new novel, or trying to run just a few feet further than you could the day before – is like trying to convince yourself that it’s a really great idea to run out into a freezing January morning in the nude and jumping into a polluted, piranha-infested lake. (Am I exaggerating a bit? Maybe. But mutant piranhas sound just about right.)

Practice has never been my strong suit. When I was a kid, I was pretty talented at the piano, but my piano teacher scared the socks off of me. She was an octogenarian patient of my dad’s who bartered medical care for music lessons. Every Thursday afternoon I’d be dropped off at her apartment for my hour of supervised practice, and almost every Thursday afternoon I’d walk very, very slowly down the very, very long hallway in her apartment building until I arrived at the elevator to graciously allow several people to take it before I did. When I could no longer convince anyone I was lurking with purpose, I’d step in it, press the button for her apartment on the fourth floor (and depending on my level of desperation, sometimes buttons one through three, too), then tiptoe down the hall to her apartment and knock ever so softly on her door. Then “knock” again. After a minute or two, I’d attempt my most innocently baffled expression and make my snail-like way back down to the lobby where I’d inform the doorman that she wasn’t answering her door. At this point, I’d have used up a good fifteen minutes of my hour long lesson, which was totally worth the painful deception because it felt like the only way I could possibly reduce my sentence. (And something told me that the doorman sort of understood what it might mean to someone to have to do twenty-five percent less time.)

But it was inexcusable. Even though my piano teacher sometimes came to the door without her wig on, frequently slapped my hands when I made a mistake, and clicked her lipstick-stained dentures before she spoke, she was skilled at what she did, and she adored me. When I quit at the ripe old age of twelve, she told my mother that she’d left her grand piano to me in her will. (Needless to say, I was quickly relieved of this generous gift, which was everything I didn’t deserve.)

I loved the piano. I loved music. I still love both. But I think that what I really dreaded about those music lessons is what they might reveal about me. Because as much as I loved music and the piano, I never practiced. And as strict and frightening as my teacher could be, the worst thing she could do was ask, directly, if I’d practiced. And because she really wasn’t born yesterday, I’d have to acknowledge that I hadn’t.

The thing is, no one in my life had ever shown me what practicing really looked like. I grew up around people who glorified raw talent and disdained poseurs. And I’m not just talking about my family. I’m talking about the education I was privileged to have, the stories I encountered about writers and great artists, the legends swirling throughout our culture about writers who seemed to look nothing like haphazardly practicing, insecure, lying-to-her-piano-teacher me.

But now I know that acknowledging my faults was what I needed to bridge the gap between frustration and fulfillment. Instead of hiding from the fact that I sometimes spend more time daydreaming about how I’ve missed my calling than I do daydreaming about my book (because obviously I need to go back to vet school in my mid-forties or learn to teach aerial yoga), or the fact that I dread encountering the half-baked writing that comprises 93% of my drafts, or the fact that I sometimes adopt a martyred attitude around the toils of laundry and proceed to sigh and blame everyone else for my failure to write – I bite the bullet and acknowledge them. Because with that acknowledgment comes softness and humor around my obvious foibles and missteps. The willingness to return to the work anyway. The awareness that practice will never, ever make perfect. And thank god for that. When it comes to art and its ability to speak from the heart about the human condition, who wants perfection, anyway?

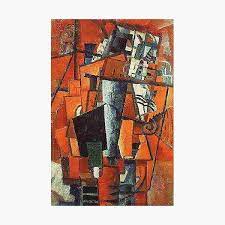

Art: Kazimir Malevich, “The Lady at the Piano, 1913”

I recognise myself completely in this description. As a child I basically swiftly gave up on anything I wasn’t immediately quite good at, and was not really given permission to fail. Since then I’ve read a whole lot of Brene Brown (gifts of imperfection) and Malcolm Gladwell (mastery over passion) and it helps me force myself to plough on, but I still never manage to do so consistently. I find myself resentful when I am writing that I can do nothing else, and when I am avoiding it (because of latent perfectionism) and I am resentful for all the reasons I am not ‘able’ to write (paid work, chores, family stuff). Both are just stories I am telling myself!

You are not alone! The other thing I needed to learn how to do was prioritize a consistent practice with VERY low expectations. When my kids were little, sometimes it was just five minutes a day to close a door and my eyes and think about my work, but it was enough to keep my oar in. Be kind to yourself, and stick with it!