It’s hard to get very far as a writer without running into some mighty strong opinions about modifiers. Many insist adjectives should be avoided at all costs; some see adverbs like the devil’s work. I once had a teacher who challenged everyone in class to remove all but three adjectives from their poems. It was an excellent exercise, but not because it removed the adjectives – it simply taught us to pay better attention to them.

My own guidelines for modifiers has less to do with quantity and more to do with quality. A modifier should result in a phrase that somehow means more than the sum of its parts. Well maybe, you might think, they’re ok, as long as they’re truly exceptional modifiers. But look at May Swenson’s “Question.” The best lines in the poem are at the end of the third stanza, and include a tidy heap of seemingly ho hum adjectives:

Body my house

my horse my hound

what will I do

when you are fallen

Where will I sleep

How will I ride

What will I hunt

Where can I go

without my mount

all eager and quick

How will I know

in thicket ahead

is danger or treasure

when Body my good

bright dog is dead

How will it be

to lie in the sky

without roof or door

and wind for an eye

With cloud for shift

how will I hide?

Even in the sparest of work, the modifier can have great presence and power. William Carlos Williams comes to mind, as does Kay Ryan. Here’s an excerpt from her “A Ball Rolls on a Point:”

The whole ball

of who we are

presses into

the green baize

of a single tiny

spot. An aural

track of crackle

betrays our passage

through the

fibrous jungle.

The point is of writing advice is that it should always work to help your voice come through more clearly. Frequently, a stiff sweep for adjectives and adverbs is the way to do this; but sometimes it isn’t. Just keep in mind that common wisdom, in writing as elsewhere, should always be an opportunity for reflection, not reduction.

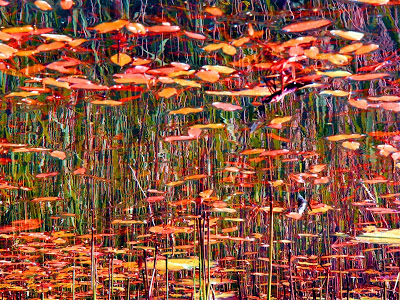

Art: Jackson Pollock

Leave a Reply