While I love/hate discussions of point of view as much as the next writer, sometimes I think they become needlessly complicated. And because writers have a teeny tiny tendency to get tangled up in their own knots, I suspect that, when choosing between first and third person, it might be useful to remember the reasons why we make such choices in the first place.

It used to be that making such choices involved much higher stakes. There was a feeling that you either had to try to follow in the godlike footsteps of Tolstoy or Dickens and adopt a narrative voice that oozed knowledge about every single character’s private and public concerns as well as the world (or worlds) they inhabited, or you were a Bronte and wrote tortured scenes about the state of your soul. Fortunately for us, there’s been a 20th century, and the lines between first and third person are far blurrier. You can write in third person as Rowling does, embracing a major main character bias; or as Chris Cleave does, switching the global perspective depending on whose scene it is. Or you can write first person as Fitzgerald did in Gatsby, using an “I” to tell someone else’s story; or actually embrace the hell out of your narrator’s unreliable qualities, a la Mark Haddon’s Christopher in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, or Ishiguro’s Kathy H. in Never Let Me Go. You can even be a Joshua Ferris and try your hand at second person (though all of us agree that speaking for more than one voice has a tendency to water down all voices).

The point is (no pun intended) that the point of view you choose matters far less than identifying the perspective(s) best suited to telling your story. In fact, you might even consider casting those rigid points of view aside and think instead about choosing a narrative voice the way a photographer chooses a lens or an artist her frame. Is a private, interior view the best way to sharpen your vision, or must you go broader and wider to do your story justice? Do you want us to see your story unfold from an outsider’s perspective or an insider’s; from far above, or from deep down in the trenches? Is it important that the narrative voice get out of the way of the action, or do its curious interpretations play a vital role in how you want your reader to experience your character’s story?

And don’t sweat it when you realize that the perspective you ultimately choose leaves some aspects of telling a story unavailable to you. My beloved graduate school advisor always used to remind us that every way of seeing is a way of not seeing. This is unavoidable in life and in art, and trying too hard to capture everything that has ever interested you about a particular subject will result in a spineless, sprawling disappointment. Making the kind of bold and powerful choices that shape great fiction always result in leaving more than you thought you could live without on the cutting room floor. Rather than mourning what you can’t say, in other words, embrace what you can, and shape everything else accordingly.

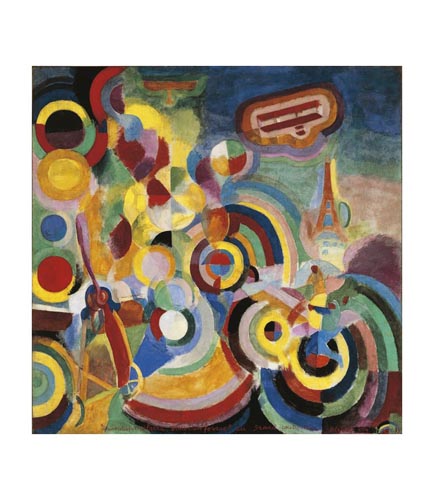

Art: Robert Delaunay, Homage to Bleriot

Leave a Reply