Many writers find the challenge of writing dialogue particularly baffling. After all, most of us are exposed to numerous voices on a regular basis. Wouldn’t it follow that we have, on hand, a bottomless wealth of experience to draw upon? Yet writers at all levels balk when it comes to getting their characters to talk to one another.

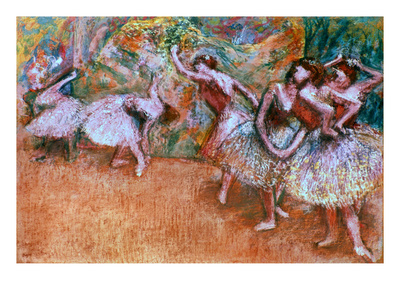

Recently, I heard an artist say that one of the reasons why we have so much trouble drawing things we see every day – like hands and feet – is because we have in our minds an idea of what drawn hands and feet look like. But if we shift our thinking, and simply jot down what we see when we’re looking at a hand or a foot – the odd curves, the shadows, the possibly unexpected shapes – we can often break through those blocks. This really struck a chord with me (and made me want to run out and draw my hands and feet), but it also reminded me of how writing, too – and perhaps dialogue even more particularly – can really take off when we remember what a conversation actually looks like, and not just focus on the words being said.

To begin with, voice isn’t just a matter of language and dialect; it’s also a matter of how we embody our voices. How we speak has as much to do with the quality of our natural voice (think Marvin Gaye vs. Judy Collins) as it does with what we actually say. Taking into account the different ways characters use their voice, too, can often make an exchange pop off the page (think thunder and lightning).

What we say is also hugely affected by how we feel in our bodies and what we do with them when we’re addressing other people. There’s a big difference, for example, between a scene in which one woman standing behind another in line watches her unload her cart with painstaking slowness before placing a hand briefly on the other’s shoulder and saying, “Here, let me help;” and a scene in which she grabs the eggs out of the other’s cart and slams them on the counter before barking, “Here, let me help.”

Building on this, it helps to remember that dialogue isn’t as much a matter of what isn’t said as what is. Two uptight, prideful businessmen will not talk about their feelings if one sleeps with the other’s wife; the cuckolded might just smile harder and invite the other to a stacked game of golf. Another example: What was Marie Antoinette not saying when she said, “Let them eat cake?”

Finally, characters must be motivated to say something. They don’t, in other words, exist just as pawns to move our stories forward. As tempting as it is to have your main character see her cousin and say, “I’m so happy to see you! The last time we were together you’d lost your baby and were thinking of suicide. How’s it going?” — it’s just not going to fly. Our jobs as dialogue writers is to capture the human through the language, not the other way around.

I’m sure you’re already getting the idea, and will come up with additional observations on your own. But it helps to be aware of the natural tendencies to think of dialogue it as only a verbal exchange, i.e., people are either talking (dialogue), or not (not dialogue). This leads to a larger point that I, for one, need to be reminded of often: that many artists get stuck when we’ve adopted overly narrow views of what we should be doing. Yet expanding our understanding of how to write our best work often goes hand in hand with expanding the work itself.

thank you.