I’m sitting here listening to my youngest make noises on the trumpet that would make a whale shudder, and it strikes me, as his teacher enthusiastically remarks on how much better he’s getting, that this is a phrase that is seriously underused. We usually reserve “getting better” as a consolation prize of a comment, something we admit to only rarely. It might perfectly acceptable, for example, to say you’re getting better after a tough flu or breakup, but we rarely allow the phrase into our more aspirational identities. If a surgeon, for example, were asked during a job interview about his operating skills, “getting better” would probably not be the answer anyone would want to hear.

And yet, isn’t it? Don’t we want to know our surgeons, too, haven’t tapped out a certain level of skill? I mean, maybe not before they operate on us or someone we love, but wouldn’t it be nice to know that even the most lauded experts among us think getting better is something worth striving toward? So maybe you’ve mastered triple bypass surgery, but what about your bedside manner? So maybe you’re a full professor at a university, but does that mean you’re no longer heeding your curiosity?

One of my favorite exercises to give my writing students is to do any particular exercise twelve times: rewrite the first sentence of your story twelve times, do the same prompt twelve times, write the same scene twelve different times – you get the idea. Usually, however, when I roll this particular chestnut out, there’s no small amount of panic in the eyes around me. But we barely have time to write as it is, their thought bubbles say, how can we take time away from our precious novel/short story/memoir to intentionally generate disposable material? Why can’t you just tell us how to get it right?

But getting better is so much more generative and productive than getting it right. Getting better involves loosening up and inviting creativity to take its seat at the table. It alleviates the all-or-nothing pressure we can place on works we’ve deemed promising and gives them the opportunity to flourish. It reminds us that producing refined work doesn’t make us better writers; writing does. And the most delicious twist of all is that the less we focus on getting it right, the more likely we are to enable the spaciousness of mind that helps us to realize our best work.

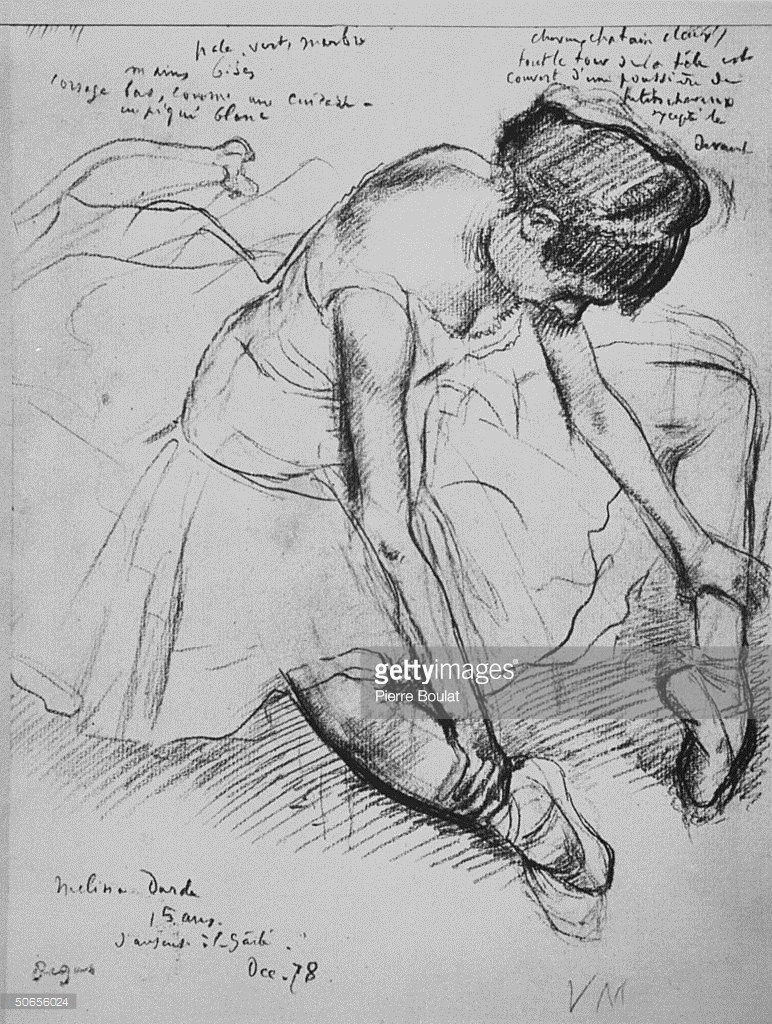

Art: “Sketch of a Dancer” by Edgar Degas

Leave a Reply