Whether you’re the type of writer who won’t begin a project until you’ve drawn up several spreadsheets and have exhausted every possible corner of research as well as your local librarian, or you prefer to tackle the work in Thurber-esque fashion, happily puttering ahead as long as you can see three feet in front of you, at some point or other, you’re going to need to define the work.

Unfortunately, unless you fully embrace this opportunity, it becomes all to easy to wind up defending the work. For instance, instead of getting very clear about your voice, and how it can be crafted into a wonderfully peculiar song, you might wind up worrying about what you don’t want to sound like, what fun they’ll make of you in The New Yorker for how shrill/dull/simpering/clinical/cold/warm it is, and how smug your third grade frenemies will feel when they read your work from atop their vulture perches. Or instead of figuring out why you are drawn to a particular subject matter and how you, as a writer, can serve it in an authentic and riveting way, you worry instead that every story worth telling has already been told, and decide to go lie in the street.

The truth is, every story worth telling has already been told, but that’s a reason to go dance in the street, because the human desire for narrative never fades, nor does our potential to fall in love anew with every voice we encounter. In other words, it’s not about how well you beat back your faults, and how cunningly you defend yourself from all critical reads by constantly henpecking every word you put on the page, it’s how gladly and intentionally you embrace the vision that most excites you.

Furthermore, your work is not a clown car, existing for the primary purpose of seeing how much of yourself and your interests can be packed within it. Just as it does not want to be burdened with every single one of your insecurities, your are not meant to be your work’s stage mother, sure that if it doesn’t shine so brightly that it wipes out the competition for years to come, neither one of you should ever show your face in public again. What it does want is for you to notice the form it’s taking, and respect that container for everything it has to offer and nothing more.

And while the work might evolve over time, breaking free of its original definitions, you must take abundant care to be sure such shifts represent creative growth, rather than the development of new armor. Because at the end of the day, the only thing you must truly stay vigilant about is your vulnerability, your willingness to tackle those things that make your heart cry out, your knees weaken, and your mind soar. Similarly, you must have the courage to own your definitions, just as you would anything else you’ve invested in, and embrace how they represent the artist you are, which is also, conveniently, the very artist you’re supposed to be.

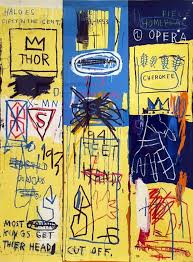

Art: Charles the First, 1982, Jean-Michel Basquiat

Leave a Reply