I’m usually not a big fan of pithy phrases to describe the human experience, but I make a pointed exception when it comes to the mental load. If you’ve never come across this phrase, it stems from an effort to define that condition so many primary caregivers suffer from; namely, the psychological weight of being constantly preoccupied with the thousand-and-one behind-the-scenes details of keeping a family and household together.

It’s been an enormously useful concept to me as a parent, but I’ve also found it useful to see it at work in my writing. In fact, I’d even go so far as to say that we’re susceptible to mental overload in any arena where our passions and ideals far exceed our capacity. And while I generally embrace the idea of shooting for the stars, it can be ever so slightly demoralizing when you realize exactly how many of them there are in the sky. And that they’re all glittering and mysterious and enticing and fascinating, and before you know it you’ve stopped reaching and are lying in the grass, dumbfounded and immobilized.

This has never been truer for me than now, six months into writing my first historical novel. It’s usually pretty challenging to juggle the mental load of a book-length fictional work-in-progress, but now I find myself navigating over five hundred volumes that comprise the existing body of work on my topic. Needless to say, there are days when all I really manage to do is play whack-a-mole with all the seemingly critical information I’ve got to sift through, but when I’m on my game, I remember two important things. One, the mental load is something I’ve had a large hand in creating, which means it’s also something I can significantly reduce; and two, when it comes to doing meaningful work, doing it all has nothing on doing it right.

To my first point: It’s tempting to feel as if the mental load is something being imposed on you. What’s worse, the more strenuous the mental load becomes, the more it feels like it’s something beyond your control. But the truth is that what we pay attention to is largely under our control. We might stop briefly at a light and feel like we can’t help but be consumed by concerns over what’s for dinner and who’s getting the groceries and how much money you’ve been spending and whether or not that mole on your daughter’s foot is really something you need to worry about and whether that stubborn bit of fat between your armpit and bra strap is ever going to go away, but you don’t actually have to. Similarly, we might feel like we’ll never get anywhere in our novel if we don’t first read everything ever written on, say, Asian tea ceremonies over the past 5,000 years before even thinking of letting our characters share a cuppa, but we don’t actually have to.

Which leads me to my second point. When it comes to doing meaningful creative work, it’s never about checking all the boxes. If it were, anyone with any kind of personal connection to their work would go lie in the street, because the more you care about something, the more you see ways you can devote your attention to it. This is true in parenting and writing and in life. The truth is, though, that one, good family dinner a week – even if it’s only twenty minutes long – is so much better that a week’s worth of menus if it means you’re able to really laugh and listen while you’re there. And knowing when to set the encyclopedic volumes or maps or voices aside to devote your attention to one thoughtful, authentically written moment is a thousand times more productive than however many more reams of paper you might have used up to flush out your notes.

Sure, things will get left aside. Important things, sometimes, in work and in life. But not getting hurt or disappointed and never hurting or disappointing anyone are unrealistic goals. Instead, set your sights on what’s manageable, which is knowing that at any given moment, you can return to the core of why you do what you do, and embrace even the smallest of victories you find there.

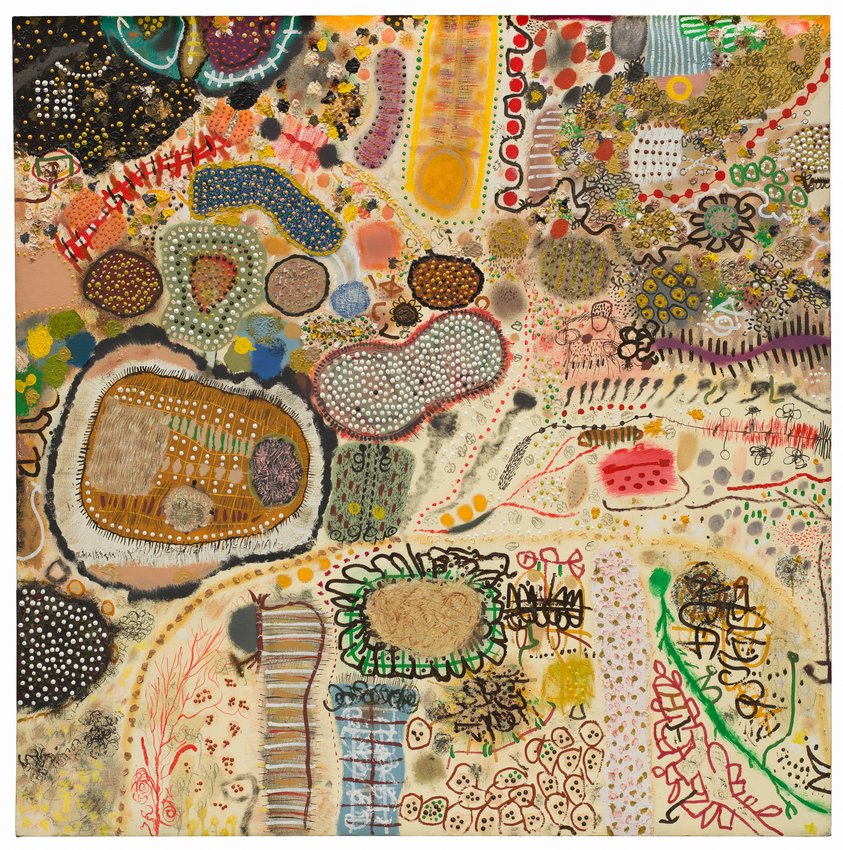

Art: Roy De Forest, Autobiography of a Sunflower Merchant, 1962-1963

The way I handled this with my first historical novel was to remind myself that I only needed to know as much about World War II as my characters would have known. They each had their own little windows on the vast forces working on them. In A Thread of Grace, I was writing about refugees from Belgium crossing the Alps into NW Italy, so the was in the Pacific wasn’t germane and most other events would only be rumors. That really helped narrow the research focus.

OTOH, the mental load included three close relatives dying of awful diseases, a teenage son learning to drive and having his heart broken by his first girlfriend, my husband leaving a secure job to start a new company, and my own personal menopause. So, yeah. It’s never easy.